Orthographic Mapping is Model Teaching

We're bad at teaching reading, but are we better at teaching anything else?

Nowadays, we can be somewhat confident that orthographic mapping is the best way to learn sight words. Readers see a word they don’t already recognize automatically. They sound it out using knowledge of grapheme-phoneme correspondences. They blend the sounds together. If they’re a strong decoder, they’ll do both those things quickly and simultaneously. Decoding is how they have identified the word; orthographic mapping is the process of making connections between its spelling and its pronunciation. With only a few decoding or encoding instances, they’ll have assimilated the word’s spelling into their existing knowledge of that word. It will be connected to what they already know about it: pronunciation, usage (syntax), definition (semantics), and personal connotations. This web of knowledge specific to each word might be referred to as the reader's schema for the word, to borrow a more general cognitive term, or as the word's amalgam, which is what Linnea Ehri has used to describe this web of prior knowledge. If the child’s grandfather has a dog, their amalgam (or schema) for “dog” probably also includes that specific dog and maybe the time it ran up and licked their face.

To the degree we’re confident about orthographic mapping today, it’s to the credit of Linnea Ehri’s description of the process. In her 2014 paper, “Orthographic Mapping in the Acquisition of Sight Word Reading, Spelling Memory, and Vocabulary Learning,” Ehri writes:

Readers must form connections between spellings and pronunciations of specific words by applying knowledge of the general writing system. When readers see a new word, and say or hear its pronunciation, its spelling becomes mapped onto its pronunciation and meaning. It’s the connections that serve to ‘glue’ spelling to pronunciations in memory.

Ehri makes clear in this same paper that orthographic mapping is not just about the acquisition of sight words (all words that can be read automatically). This connection-making process also aids in learning new vocabulary words that are not in our spoken lexicon. In a 2008 study, Ehri found that being taught the spelling of new vocabulary words was more effective than hearing the word extra times. Because phonics lets us easily translate spelling to sound or sound to spelling, having a word’s spelling is essentially a form of dual coding for learning new words. By having both the spelling and the pronunciation, a word’s meaning can be connected to a stronger web of knowledge, which makes it easier to remember. The directionality of speech-to-spelling or meaning-to-spelling or speech-to-meaning isn't as important as all elements being present and interwoven. We want to build a web between the word's sound, usage, meaning, and spelling. To use Ehri's term, we want to form more complete and better-connected amalgams.

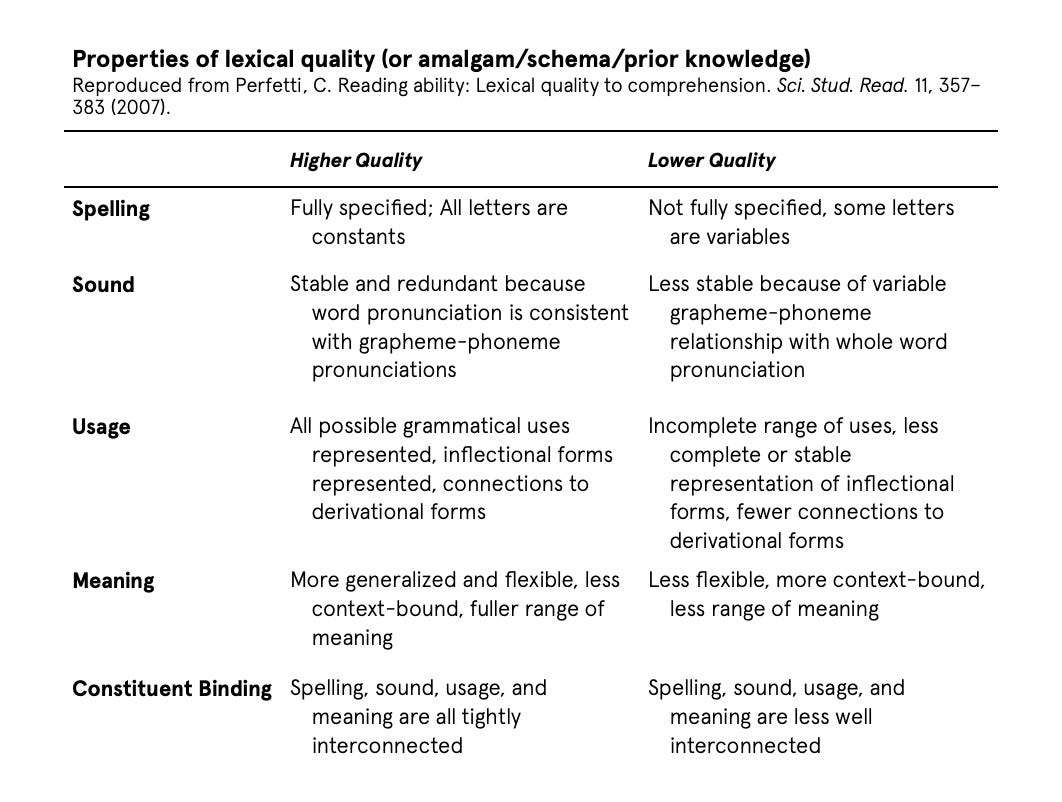

Other researchers have written about this as well, sometimes using different terminology. Charles Perfetti hypothesized that having a stronger “lexical quality” in our minds for a word allows us to more quickly and meaningfully comprehend it, its use in a sentence, and the sentence depending on its use. Higher lexical quality (or “amalgams” or “schema” or “prior knowledge”) means that when we read a given word in a sentence, we have a better chance of understanding it in its specific context. Perfetti charted the different components of a word's lexical quality, reproduced below:

Orthographic mapping, applied to this idea of lexical quality, is the forming or tightening of connections between a word's sound and its spelling. This strengthens the quality of both components and helps create a flexible amalgam because our word recognition depends only on the constant components of the word- its spelling and pronunciation- and not on variable ones- its meaning and grammatical usage. For example, the letters in “bear” will always represent the same sounds in “bear.” We can, after decoding, use grammar or meaning (or pictures) as feedback to confirm we decoded the word successfully, but critically, we must first form connections between spelling and sounds. Those are what remain stable independent of the context. If the reader uses other sources of information to decode the word, even if they do successfully decode it, they will fail to improve their amalgam of the word.

For example, using a picture or contextual meaning to navigate from the letters of “bear” to its pronunciation is unstable and inconsistent. What if we have to read “apple trees bear fruit”? The work we did previously is of little help and we’ve not improved as a reader. In reading acquisition, sentence-level meaning is actually often the feedback mechanism telling us we decoded successfully. The meaningful learning we care most about is the connections between a word’s letters and its sounds. Text comprehension is not the only goal of reading in the early years, and it matters terrifically how that comprehension is achieved.

Reading is a specific case of a general principle

However, the importance of making connections between new and existing knowledge is hardly particular to reading. Really, orthographic mapping might be viewed as a specific case of a general theory: David Ausubel’s theory of assimilation. Ausubel argued that when we learn something new, we assimilate it into our existing web of prior knowledge. Our ability to encode something new in our long-term memories depends on making connections to what we already know. New knowledge can be more easily learned when it's more meaningful: when it has greater connections to existing knowledge.

Ausubel, ever promoting the importance of prior knowledge, even anticipated how efficient sight word learning must draw upon the reader’s existing spoken lexicon:

The most salient psychological characteristic of learning to read is the dependence of the learning process on the previously acquired mastery of the spoken language...[the reader] tries to establish representational equivalence between new written words and their already meaningful spoken counterparts. (Ausubel, 1968, p. 69).

For Ausubel, reading was actually the easy thing. Without getting into a discussion of biologically primary and secondary learning, Ausubel saw learning to speak as a greater achievement than learning to read:

Because of the denotative meanings and syntactic functions of the component spoken forms, learning to read obviously constitutes a less significant cognitive accomplishment than the original learning of the spoken language. (Ausubel, 1968, p. 69, emphasis mine).

When we learn to read, we have some significant assets to help us: a fairly lawful code of phonics to reproduce sounds from letters and fairly developed oral language abilities. Unlike Ausubel, who made this claim in the 1960s, we would argue today that the beginning reader has not yet “acquired mastery of the spoken language” and that reading and language comprehension are mutually reinforcing for many years after we first learn to read. At the start, reading is definitely the beneficiary of our knowledge of spoken language, but we know, from the previously mentioned study of vocabulary learning or studies of language in children’s books, that reading strengthens our verbal language abilities (Dawson et al., 2021; Nation, 2017).

I think because reading is so important and because we have accumulated so much research on how it is learned, it’s easy to assume it's difficult to learn. Ausubel is suggesting that, from a cognitive view, it may be one of the easier things. Spoken language means we already know a lot of the right answers for our decoding attempts, so we have this sort of terrific built-in feedback to allow for such a thing as what David Share named “self-teaching.” Almost the entirety of our sight word lexicon is acquired via this process of self-teaching, suggesting it’s not too difficult once the prerequisites for orthographic mapping are in place. And, throughout our educational history as an English-speaking people (including possibly the present), it has been popular to view reading as a naturally emerging behavior, suggesting reading appears deceptively easy. Ironically, I think the prevalence of misunderstanding learning to read can just as well lead us to mistakenly view it as prohibitively difficult.

Possibly, reading is easy relative to other domains, but, because it is so powerful, our standards for proficiency are vastly higher than anything else we expect kids to learn. Many kids read fairly complicated text with near-perfect fluency at a rate of 100 words per minute before they know that 6x7=42. Lots of kids know how to spell picture and thought and vacation before they know how clouds form. Some significant minority of kids even manage to become proficient readers despite terrible literacy instruction! Because reading provides so much leverage for learning other things, we rightly prioritize it to an extreme degree. But that does not inherently mean it's difficult or unique. Compared to everything else we try to teach, we actually do the best with reading (and that should scare us). Reading is maybe similar to driving a car: it’s not that hard; it’s important to be explicitly taught; and it’s incredibly dangerous to assume people will learn naturally.

So what?

I hardly suggest that we relax about teaching reading. While it’s possibly one of the easier things our schools need to teach, it’s very important to be very good at it, and we don’t teach it very well. Yet I suggest that tells us more about the overall quality of our teaching than it does about the difficulty of reading as a discipline. Because we don’t really do anything else better.

We should be cautious about assuming other things will be learned as easily as sight words. There is no built-in immediate feedback mechanism for learning that 6x7=42 the way there is for decoding the word “mechanism.” With three or four decoding exposures to a new word, it tends to become a sight word. Each decoding attempt is a form of rehearsal where the meaningful connections between the word’s letters and its pronunciation (which is already securely known!) are strengthened. The act of reading does a lot of the work of feedback and rehearsal for the teacher, but we don't have strong self-teaching mechanisms for most things we teach. In most other areas, we need to ensure students get accurate, immediate feedback and multiple opportunities to rehearse the connections between concepts.

Also, note that part of the reason sight words are learned with so few exposures is that the rehearsals are all meaningful: they strengthen the connections between the word's spelling and its sound. Rote rehearsal (whole-word learning) would be less efficient and take more repetitions because fewer connections are being made. So, when we have students rehearse in other areas, we also need to make sure the rehearsal is meaningful. As always, we need to determine what the learner already knows and figure out how we can help them connect the new knowledge to the prior. Rehearsal should then focus on the novel concept's relationship with prior knowledge, rather than only on the new thing itself.

In other subjects, we can never provide feedback as precisely and immediately as when readers decode a word and understand its place in a sentence, but we can aim for something similar. And it's no accident that highly effective instructional approaches like Englemann’s Direct Instruction apply these principles: an instructional sequence that allows for meaningful connections between prior knowledge and new concepts, and high rates of rehearsal with immediate and precise feedback. DI is essentially trying to recreate features inherently present in sight word learning.

Despite significant missteps and misunderstandings among literacy educators, we know more about teaching reading than about teaching anything else, and we're better at it than we are at anything else. I don’t think it’s the case that learning to read is inherently different and apart from learning to do other things, but we have to be careful to avoid taking away the wrong lessons. Many educators historically have viewed the self-teaching aspect of literacy as evidence of learning’s natural emergent qualities. Rather, I believe, the effectiveness of orthographic mapping should remind us of the importance of building prior knowledge, giving prompt and precise feedback, and planning for lots of meaningful rehearsal. Evidence-based literacy instruction actually does work really well, and I think generalizing the right lessons from how kids learn to read has some merit as a way to become better teachers.

Works Referenced

Ausubel, D.P. (1968). Educational psychology: a cognitive view. Holt, Rinehart and Winston: New York, 69.

Dawson, N., Hsiao, Y., Tan, A.W.M., Banerji, N., & Nation, K. (2021). Features of lexical richness in children’s books: Comparisons with child-directed speech. Language Development Research, DOI: 10.34842/5we1-yk94

Ehri, L.C. (2014). Orthographic mapping in the acquisition of sight word reading, spelling memory, and vocabulary learning. Scientific Studies of Reading 18(1), 5-21.

Nation, K. Nurturing a lexical legacy: reading experience is critical forthe development of word reading skill. npj Science Learn 2, 3 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-017-0004-7

Perfetti, C. (2007). Reading ability: Lexical quality to comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 11, 357–383.

Rosenthal, J., & Ehri, L. (2008). The mnemonic value of orthography for vocabulary learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100 , 175–191.